“They are so very different from us”

Edit András – Springerin

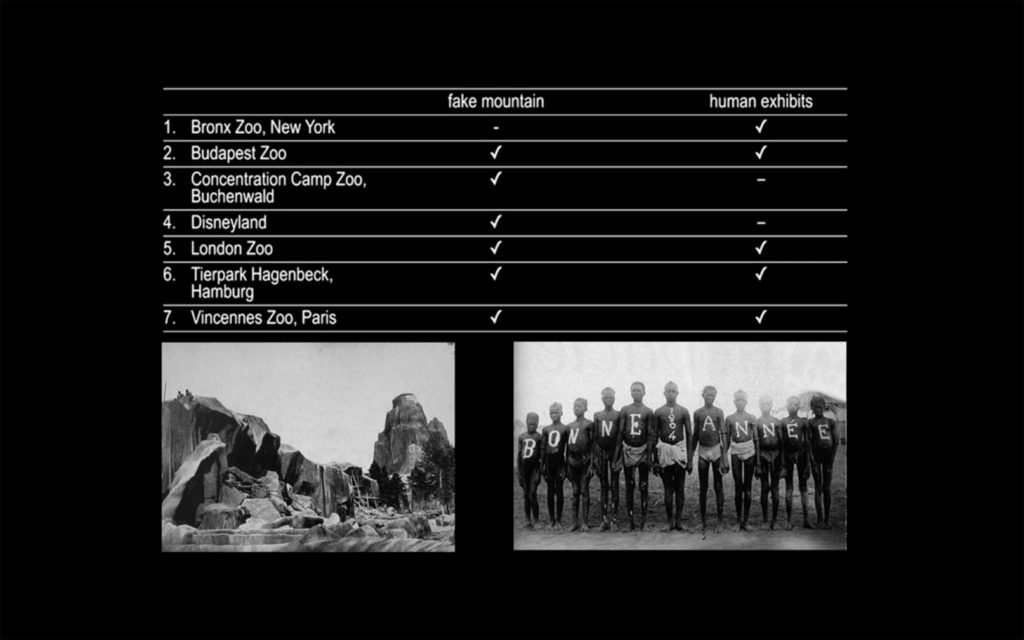

(…) In 2012, Szabolcs KissPál created a docu-fiction, entitled Amorous geography, for the publication Zoo-topia. The docu-fiction was about zoo architecture as a taxonomy of national representation. In the video the colonial imagination of the late nineteenth century is shifted and adapted to Transylvania, Hungary’s dreamland, a “lost paradise” detached from the country after the Trianon Peace Treaty of 1920. Contemporary artists generally avoid the subject, as it has been appropriated and politicized, including by the extreme Right. The interwar revisionist sentiment that permeated all segments of culture was suppressed under the socialist regime, only to come back again with a vengeance after the collapse of the socialist system. The drive for reconstructing the pre-Soviet past as it is now perceived is apparent in the re-establishment and support of conservative, religious and nationalist culture represented by the Hungarian Art Academy (HAA), a kind of cultural shadow ministry inscribed into the constitution. The increasing reach of the Academy’s power has prompted contemporary artists to organize several protests. The other form of jumping back in time is the reconstruction of Budapest’s number one symbolic site, Kossuth Square, which surrounds Parliament. The aim being to recreate the look that the square had in 1944. The revanchist Trianon discourse provided, and continues to provide, a container for projecting post-war feelings and desires, such as melancholy over the loss of an imagined grandeur; the pain of defeat and humiliation, as well as dispatching with any sense of responsibility. By extending victimhood to all sufferers of the Nazi regime, the recently erected Nazi occupation monument in Freedom Square, the other key symbolically charged site in Budapest, denies any accountability for the Holocaust. From the very first moment of its construction, it triggered continuous resistance and galvanized a counter monument, named Living Memorial.

The contrast between the vertical Nazi occupation monument, made of materials intended to last and safeguarded, and the horizontal Living Memorial, made of fragile, ephemeral materials, is striking and echoes the power imbalance between officially propagated culture and its opposition.

KissPál takes the fantasy of Transylvania as the nest of essential Hungarianness to the extreme in his video, with a scene that shows Admiral Horthy (1868-1957) examining the best available examples of the species to exhibit in the zoo. The artist – one of the initiators of the Living Memorial – breaks the illusion of the sacred bond between the caring “mother-state” and the helpless kinsfolk beyond the border of the shrunken motherland. Thus, KissPál reveals the hidden colonial nature of the overheated affection that can be successfully mobilized in any time of crisis or conflict in order to distract attention away from real problems. By way of a kind of psychoanalytic assessment of unconscious motivations and desires that underlie this love-affair, the artist reverses the narrative of passive victims suffering the effects of an unjust peace treaty into the narrative of an active and aggressive colonial power unable to cope with its own historical accountability. Lifting the veil covering the dark side of modernity – the invention of the “savage”, the Other in the concept of “civilization” – the work calls for reflective re-evaluation and renegotiation of this (chosen and dearly embraced) traumatic event. (…)

Eurozine